Most funeral traditions in ancient China, just like any religious traditions, were surviving on from person to person. All of these practices fall under the term Chinese Folk Religion. Since the religion itself was not organized, burial traditions varied greatly. Commonly, though, there were certain elements of focus on helping an ancestor to move forward to the afterlife. Secondly, there was a heavy emphasis on the relations between the dead and the living.

We additionally discuss the effect of Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism and even communism in shaping modern Chinese Folk death beliefs and customs. Thereafter, this article focuses on modern death practices in China, such as the significance of joss paper. Finally, we discuss the long history of funerary art in China, focusing on the Imperial Terracotta Army.

Chinese Folk Religion is an umbrella term that includes hundreds of practices throughout China. It also includes certain deities and traditions linked to Chinese mythology of the dead. For instance, the Heibai Wuchang (translating to Black and White Impermanence) is a duet of deities. They are, fittingly, wearing black and white. These two gods have the duty of accompanying the souls of the dead to the next world. Additionally, the Hebai Wuchang answer to Yanluo Wang who is the Supreme Judge of the Underworld.

Finally, other deities of Chinese mythology linked to the death are the Ox-Headed and the Horse-Faced guards of hell (‘Diyu’). The role of these two guards is to actually hunt down souls that should not be on earth anymore. After that, they bring the souls to Diyu so they can receive their final judgement. Moreover, they may also function as messengers of the Supreme Judge.

In most societies humans have created belief systems that focus on life or existence after death. Especially in Indic and Abrahamic religions, this has an element of individual salvation. In other words, these religions highlight the importance of the person focusing on saving their soul. However, pre-modern China, especially before the influence of Buddhism, followed different approaches when attempting to discuss death and beyond death beliefs.

Originally, many Chinese highlighted the biological link between themselves and their ancestors. Moreover, they focused on how their ancestors provided them the gift of life, sacrificing their own material pleasures. That sense of sacrifice created certain filial obligations towards one’s parents. In other words, since your parents and elders made sacrifices for you, you are obliged to return the favor. These obligations did not stop, however, with the death of one’s parents. On the contrary they became even more pronounced: honoring ancestors was crucial since they could directly influence the life of the living. Additionally, these obligations also extended not only to children, but often to grandchildren too.

This means that there was an elaborate afterlife care in pre-modern China. This form of care included significant rituals and ceremonies, mourning practices and ancestral rites. It was crucial that the dead ancestor received these rites and prayers otherwise their tormented soul could turn into a vengeful ghost bringing misfortune and illness.

All of this indicates an Ancient Chinese system of reciprocity between the dead and the living. In other words, there were mutual obligations between a person and their ancestors. A satisfied ancestor was a positive influence in people’s life, protecting them and providing a better quality of life. As a result, receiving a proper burial and following the mourning customs was crucial. This also involved a continuous offer of food, drinks and gifts to the ancestors. On the contrary, the tormented souls we mentioned before, turned into hungry ghosts. Such entities could even cause financial misfortune to the family or even the whole community.

Therefore, instead of focusing on individual salvation, older Chinese death customs dictated the importance of honoring one’s ancestors as a means of keeping the self, family and even community safe and prosperous.

As we discussed above, Ancient Chinese venerated and feared their ancestors. After all, there is proof of afterlife care in China already since the Shang period (1500-1050 BC). As a result, this contributed to the creation of the system of dual souls. The duality of Chinese philosophy at the time focused, after all, on the yin and yang dichotomy. This refers to the notion that all existence is a result of the interaction of passive (‘yin’) and passive (‘yang’) elements.

As a result, ideas of yin and yang duality were present in the conception of souls. The yin soul (‘po’) was more material, while the yang soul (‘hun’) was not of this realm. That meant that the po that originally was at the body, was now linked to the grave. This was the case because the po needed something tangible and material. The ethereal hun resided at the ancestral table, a commemoration object kept at the family’s house.

In many regions there were also multiple hun and po. The multiple souls approach allowed for Chinese to be more flexible when interpreting the behavior of ancestral spirits. For example, an ancestral spirit could sometimes be benevolent while other times malevolent. In order to better explain that, many ancient Chinese adopted these multiple souls systems.

Although the Chinese had elaborate death rituals, the same does not necessarily apply to their view of the afterlife. The ancestral existence remained largely open to interpretation. However, there were certain ideas of how the spirit world looked: it was a dark, murky realm while at the same time resembling our world. That meant that, for example, the souls needed to work on improving their conditions but also used food and money. There was even bureaucracy that they had to take care of! This bureaucratic dimension was later greatly expanded with the arrival of Buddhism in China.

Gradually, religions favoring individual salvation such as Buddhism started spreading in China. Therefore, the Chinese of that time were forced to either accept them and abandon their older practices of ancestral obligations or try to compromise between the two systems.

Buddhism was one of the first influences in China that shifted, to an extent, the focus from the community to the individual. That took place at the same time as increased urbanization of Chinese societies (at least since the Song Dynasty, 10th century). Lay Buddhists, referring to everyday Buddhists and not monks, focused particularly on ideas of salvation and rebirth.

Other religions also rose in modern times and were in even starker contrast with the hierarchy of Chinese society. These were often syncretic religions, meaning that they were adopting elements from different religious beliefs combining them together to create new approaches. Some examples include the White Lotus of the final imperial era but also the Way of Unity and the Falun Gong movement in modern China. Additionally, the popularity of these religions also caused a backlash from Chinese governments partly due to their individual focus. Some of these syncretic religions combine ideas of Confucianism with practices of Taoism and Buddhism.

Interestingly, although Buddhism’s influence cannot be denied in China, there are notable exceptions. For example, Chinese continued using burials although they accepted many Buddhist notions regarding death. However, since 1949 when the Communist Party ascended to power, cremation has become very popular in China. As a result, simple, more practical funeral rituals were favored. Nowadays, cremation is a common death practice in China (45,6%), especially in the largest urban centers. Inhumation has returned, though, as the most preferred option.

As we just mentioned, the Chinese Folk Religion is more of a general term. However, over time rites and funeral practices started becoming more cohesive. Specifically, scriptures of Confucianism started becoming the norm for many funeral settings already from the 13th century. Many Han people also used the standardized rites when interacting with other ethnic groups as part of their identity as Chinese.

Researchers have identified nine characteristics of the standardization of Chinese funerals. Firstly, it is significant that close relatives make the death public either by lamenting or using funerary banners. Secondly, the appropriate color during a funeral was white. It was also important that the family cleaned the body of the deceased with water during a ritual. They would additionally offer food and paper money to the dead. Thereafter, they would make an ancestral tablet, always to be kept at home. Additionally, relatives would pay Taoist or Buddhist priests specializing in rituals to help the soul of the deceased. Music had to also be present during the procession in order to soothe the spirit of the dead. The coffin of the dead relative was airtight. Finally, the burial at the designated site signified the end of the funeral.

Another crucial element of such a funeral often was geomancy. As mentioned earlier, Chinese traditions had close relations with their ancestors as their life was a gift from them. Similarly, the body also was part of that gift and needed to be treated with the corresponding respect. The bones of the deceased were especially important since they symbolized the eternal link between the deceased and their descendants.

Therefore, a specialist in geomancy (or ‘feng-shui’) had to decide what is the best burial time and site. This also brings us back to the notion that the po soul lingers close to the grave. Interestingly, Chinese geomancy has managed to survive many years of Communist disapproval.

We already discussed some common elements of Chinese funerals as they were established during the standardization of practices. Nowadays, even irreligious Chinese often practice death folk rituals.

The set of rites often depends on the cause of death, the age of the deceased and more importantly on the social status of the deceased. This also includes whether they are married or not. Generally, funerals take place during seven days. The funeral dress code dictates that red should not be present since it traditionally has connotations of happiness. After all, red is the color designated for weddings in China. Additionally, repeating certain gestures three times is significant.

Certain Chinese traditions support that an elder should not show respect to a younger person. Therefore, if someone dies young – and unmarried – that applies to them. The family, thus, does not bring the body home but at a funeral parlor instead. Since the unmarried person most probably had no children, no one can officially offer them the appropriate funeral rites and prayers. As an extension of these beliefs, children are sometimes buried in complete silence.

Using money for funerary purposes has a long history in China. For instance, dark coins or simply burial money, was a fake currency that the people of the Shang Dynasty used (2.000 BC). Originally that currency was cowrie shells that aimed to bribe rulers of the underworld. Gradually though, Chinese started using clay money since it was cheaper. This way they aimed to discourage grave robbers from trying to violate the tombs of their ancestors.

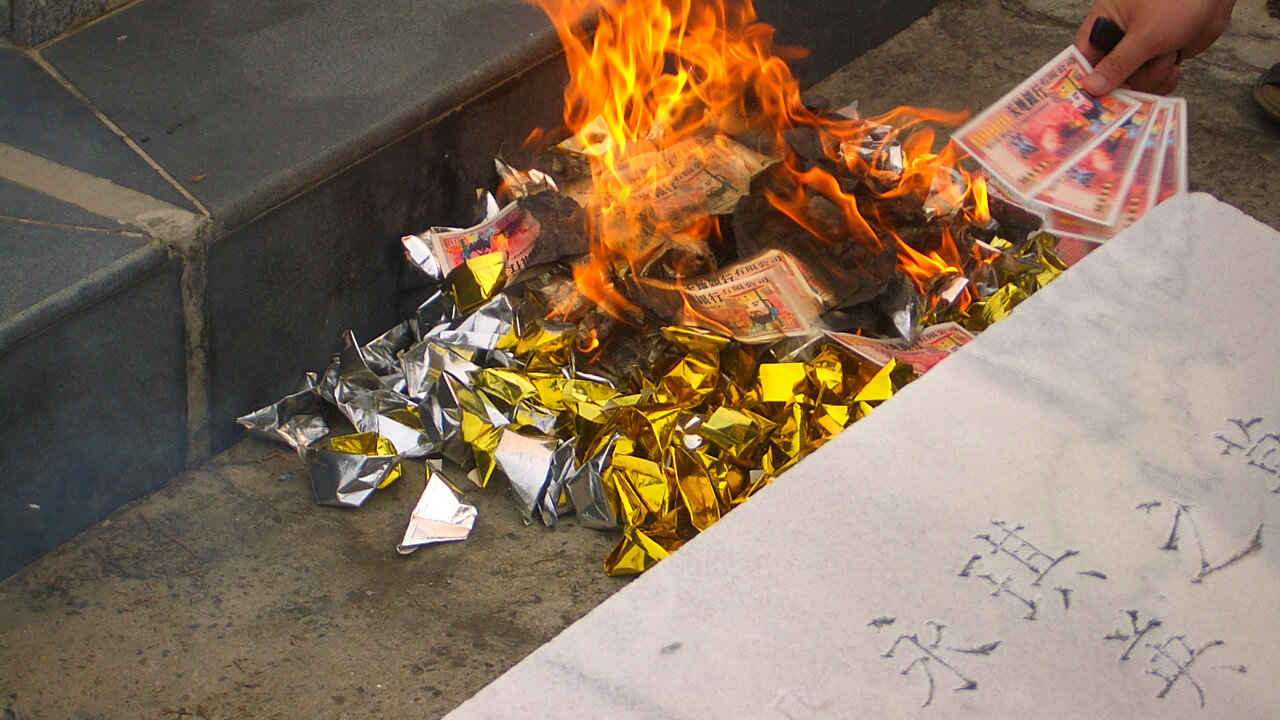

Around the third century people in China started using paper burial money instead. This was an early form of joss paper used nowadays. Relatives burn the joss paper in order to send it to their dead relatives. This imitation paper money is often made by a company called the Bank of Heaven and Earth, highlighting that these products are for both this realm and the next.

Relatives pay respect to their ancestors on many occasions throughout the year. None is perhaps as grand and as important as the Qingming Festival (translating to tomb sweeping). This is a special memorial day for most Chinese communities both in China and internationally.

During the Qingming Festival, Chinese visit the graves of their loved ones and clean them – thus the name. It is also common to pray and make food offerings. Finally, they may burn incense and joss paper during this occasion too.

Many civilizations have used art to decorate burial sites or even build monumental structures. Chinese funerary art also follows such patterns, exhibiting a rich history of art in death practices.

In early Chinese history, royalty received grave goods and art similar to that of Ancient Egyptians. For example, they were using expensive jade burial suits. Additionally, most imperial tombs in China have a spirit road expanding often for kilometers before reaching the burial site. These spirit roads include elaborate statues of both humans and animals and are meant to function as guardians. Tombs of the Han Dynasty included mostly statues of chimeras and lions. This changed though in later years, with more variation of statues being excavated.

There is, though, no other form of Chinese funerary arts more famous than the Imperial Terracotta Army. Known also as simply the Terracotta Army, it is quite literally what the name indicates: an army of elaborate statues made of terracotta clay. The army belonged to the First Emperor of China, Qin Shi Huang and was buried with him after his death around 210 BC. Furthermore, the Terracotta Army did not just function as a grave offering but was meant to protect the Emperor in the afterlife.

Interestingly, the Army was found completely by accident in 1974 when farmers of Lintong County started cultivating fields. Moreover, the numbers of the army correspond to those of an actual army. For instance, in the three burial pits of the tomb there were over 8.000 soldiers. Moreover, there were over 130 chariots with their 520 horses and 150 cavalry horses! There were even civilian statues present in the burial site such as acrobats and musicians. The height of the soldiers depended also on their rank within the army, with the generals being the tallest.

Emperor Qin started planning the burial site at the age of thirteen, just after his coronation. Sources report also that over 700.000 workers were forced into working to prepare the Emperor’s tomb. They also poured mercury simulating 100 rivers in honor of their Emperor. Some researchers thought that the extensive use of mercury was a false report. However, testing the local soil showed a particularly high level of mercury!

Finally, it is worth mentioning that the Terracotta Army is part of a huge necropolis. This area is estimated to be almost 100 square kilometers (40 square miles). Additionally, it includes a scaled down version of his own palace. Nowadays, the necropolis is open for visitation and is part of an imperial park.

We hope you learned something new regarding this country’s death practices!

If you want know more about other syncretic funeral practices, feel free to check out our Cuba or Brazil article! We also have other articles focusing on ancient civilizations such as Greece or Ancient Egypt. Finally, for more on the effect of Confucianism in Eastern Asia, have a look at our South Korea article!

The average mixed death rate of China is 7,1 per 1.000 people (2019).

According to Chinese traditions, the funeral could take place even up to seven days after death. In the meantime the family is preparing the body and holding rituals.

Historically, Confucianism, Taoism and, later, Buddhism heavily influenced Chinese religious affairs. Together they are the “three teachings”, present in everyday Chinese life. Nowadays, China officially follows state atheism. However, many Chinese practice folk religions. For example, although the majority (73.56%) of Chinese identify as atheist, they often practice Chinese folk customs. That corresponds to over 1 billion people!

Additionally, the Chinese government recognizes five religions. These are Buddhism (15,87%), Taoism (7,6%), Catholicism and Protestantism (2,53% together),as well as Islam (0,45%). During the last 20 years, there have also been efforts to more officially include Confucianism and Chinese Folk religion.

The rate of utilized organs in China is not necessarily clear. However, we can get a good idea considering that the rate of deceased donors was 4.16 per million people (2019). That corresponds to 5.818 actual donated organs that doctors may have used for transplantations.