Egypt

Ancient Egyptian Beliefs & Rituals

Introduction

For Ancient Egyptians, death was inescapable but in a way could be endured. Some of the most crucial death beliefs of the Ancient Egyptians focused on the underworld, the role of certain Gods in the afterlife, the components of the soul and rebirth. Additionally, these beliefs corresponded to certain rituals and ceremonies, often described in the Book of the Dead. This article explores all of these ancient rituals as well as the process of mummification. Finally, we provide a brief timeline of the evolution of funerary practices in Ancient Egypt.

Death Beliefs

Underworld & Rebirth

The underworld was accessible to the deceased through their own tomb. Entering the underworld (“Duat”), the soul of the dead found itself in a hallway with impressive statues, many of them devoted to the God Horus. Of course, the underworld of common people and royalty was not the same. However, souls met the God Osiris, who would then decide if the deceased led a virtuous enough life to be granted access to a blissful, peaceful afterlife.

Light as a feather

However, the most important perhaps trial a soul faced in the afterlife preceded meeting Osiris. It was the trial of the Goddess Ma’at who passed judgement with her scales. Specifically, the dead need to recite the list of 42 Negative Confessions – in other words denying committing 42 crimes or sins. Then the Goddess placed the heart of the dead on one scale. On the other scale she added a feather, which if the heart outweighed then the person could not proceed to the afterlife. If the deceased’s heart was lighter than the feather, they could meet Osiris in the Field of Reeds.

Field of Reeds

During the 5th Dynasty, Egyptians started believing in the concept of a Field of Reeds.

This Field represented the end destination of the journey of the virtuous souls. Moreover, the deceased who reached the Field of Reeds, were the ones that were offered the privilege of rebirth. Egyptians also imagined this Field similarly to how many Abrahamic religions imagine paradise: Lavish grasslands with wonderful waterfalls and rivers. Additionally, water separated the Field of Reeds in different island-like regions that could be navigated only by boat.

The abundance of water in the Field of Reeds is also linked to rebirth and especially having access to the river Nile. After all, the Nile and its adjacent farmlands were a primary source of prosperity of Egypt.

Gods & Men

Moreover, it was not only righteous souls that ended up in the Field of Reeds, but also Gods themselves.

Spending time with Gods and eating the same foods as them gave these souls God-like characteristics. One of these divine attributes was the ability to communicate with other relatives they had previously passed away and even with the Gods.

Soul in Ancient Egypt

One of the most fascinating Ancient Egyptian beliefs was about the composition of souls. Specifically, Egyptians saw souls of the sum of many different parts, all responsible for a different function. In Ancient Egyptian cosmology the world was created by the God Atum. He infused magic with everything on earth to provide order to the existing chaos.

As a result, everything – and everyone – contained some residual magic within. For humans that was the soul. Furthermore, the number of different parts of the souls varied depending on the period or the Dynasty. There were always, though, at least five parts in most funerary traditions.

Khet, Sah & Ib

First of all, Khet refers to the physical form that the soul was attached to. Without it the soul could not be judged in the underworld. Furthermore, Sah is a spiritual body formed by the soul and that interacts in the afterlife with other souls or Gods. Moreover, the soul can take the form of Sah only if all the funerary rites and rituals are successful.

The following part of the soul was a particularly significant one. Specifically, the Ib is the heart and Egyptians thought that it takes shape from a drop of blood of the mother’s heart. Because of that, the Ib was responsible for people’s emotions and thoughts.

Ka

One of the most well-known parts of Ancient Egyptian souls was Ka. It refers to the vital essence that separates the dead and the living. The Goddess Meskhenet – or Heqet depending on the region – blew the Ka into infants on the moment they were born. After death, the Ka left the body. However, food and drinks sustained the Ka which explains Ancient Egyptian grave offerings. In addition to Ka,

Ba & Akh

Another particularly interesting soul-part was Ba. It was responsible for each person’s uniqueness and personality to an extent. Like Ka, Ba also left the body after death often in the form of a human-headed bird. Moreover, the Pyramids of the Old Kingdom were a symbol of their owner’s Ba.

Additionally, the Ka and the Ba were reunited in the afterlife in order to rebirth the Akh. This referred to the person’s intellect. The living had to sustain the deceased’s Akh through offerings and rituals, in order to turn the dead into a sort of ghost.

Especially during the 20th Dynasty, Egyptians believed that these dead still had an influence on the matters of the living and could intervene if summoned or provoked.

Shut, Sekhem & Ren

A lesser known but fascinating soul portion was the Shut. This was also the person’s shadow. Shadows were important in Ancient Egypt since they were thought to contain part of the person’s identity. Additionally, the assistant of the God of death, Anubis, was also a shadow. Another mysterious part of souls is the Sekhem. Egyptologists often describe it as the living force or a power that preserves the soul in the underworld.

Finally, a particularly important soul fragment was the Ren which was an Egyptian’s name. More than just a name, though, it represented the deceased’s memories and experiences. As long as someone spoke the name of the dead, their soul remained alive. This is why the name was present in all burial grounds, so that the soul may be preserved.

Gender transformations

In certain ways, women in Ancient Egypt had to post-mortuary adopt more male characteristics. These gender changes did not take place on their bodies but on their tombs or burials chambers. But why was that the case?

Egyptologists have supported that manhood was often celebrated in the afterlife. Even Gods, and especially Osiris, were praised when they exhibited bold manly characteristics. In a way, manhood was linked to rebirth in the afterlife. Moreover, statues of Gods were often made with an erected penis in order to highlight their manhood, and thus their potency to resurrect.

Since women – or women’s statues – could not exhibit such attributes, they had to find other ways to avoid not achieving Rebirth and eternal life. For example, they would add the name Osiris on their tombs or adjust their names in order to be more masculine.

Spells, Rituals & Death Customs

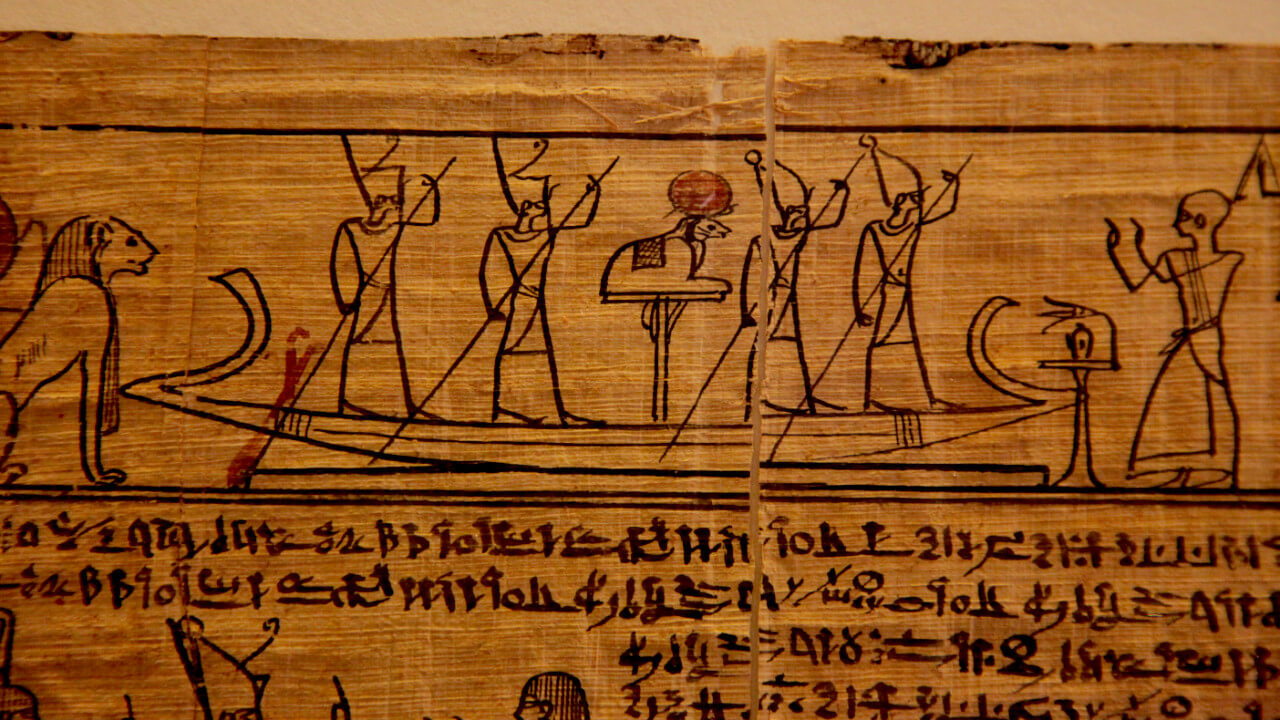

One of the most iconic pieces of Ancient Egyptian funerary tradition is the Book of the Dead. This book is a large collection of prayers and magical incantations that aimed to assist the soul of the deceased with their journey in the underworld. Let’s explore some of these ancient rituals.

Book of the Dead

However, the Egyptian title of the book is actually The Chapters of Going Forth by Day, with forth referring to attempting to reach rebirth. Although Egyptians used mostly papyri for the Book of the Dead, it was also found on tombstones, walls and even scarabs. Such papyri from the New Kingdom could easily reach 75 feet (roughly 23 meters)!

The Book also contained illustrations of every single spell that the deceased could use in order to safely traverse the chaos of the afterlife. Additionally, due to the lavish descriptions we can assume that the average Egyptian could not afford such elaborate funerary rituals. No, these ancient rituals were accessible to some selected few.

Navigating the Underworld

The afterlife’s chaos we mention above was always present in the underworld. That was what souls needed to navigate in order to reach Osiris.

The Book of the Dead, provided advice and, in a way, navigation tips. Interestingly, it was used like an afterlife GPS, so to speak. Finally, it described many ancient rituals the living needed to perform in order to assist the dead. The most characteristic one, was perhaps the Opening of the Mouth ritual.

Opening of the Mouth

This ancient ritual already took place in the Old Kingdom and continued all the way to the Roman Era of Egyptian history. A mummy or a statue depicting the dead was, symbolically, reanimated since it opened its mouth. By opening the mouth, Egyptians could sustain the soul of the dead by providing much needed nutrition. They could, additionally, defend themselves during the weighting of the heart trial.

Furthermore, the living used special tools to open the mouth during this ancient ritual. This included an Adze (a ritualistic axe-like tool), a Peseshkaf (a serpent-head knife) and various artifacts. Egyptians also used a calf’s leg on the painted lips of the coffin. Finally, the dead also needed to help with the ritual by using a spell in themselves. Part of the spell reads:

My mouth is opened by Ptah,

My mouth's bonds are loosed by my city-god.

Thoth has come fully equipped with spells,

He looses the bonds of Seth from my mouth.

Atum has given me my hands,

They are placed as guardians.- Book of the Dead

Funeral Customs

Embalming the Body

Egyptians often embalmed the corpse or tried to preserve it in order to prevent decay. That was not the case if the wife of a high-ranking official died, so that nobody will violate the body. Additionally, if the deceased was himself high-ranking, then it was common for grieving Egyptians to spread mud on their faces.

They would then walk around the city lamenting and hitting their chests as a sign of grief. Furthermore, if the person died by drowning or getting attacked, Egyptians embalmed the body immediately. Due to the nature of death, only priests could touch the body.

Enactment of Judgement

Part of the funerary rituals was also the Enactment of Judgement ceremony. That looked almost like a play with different people being assigned to the roles of Gods such as Osiris, Horus, Anubis and Set. The play was about the death and dismemberment of Osiris by his brother Set and the efforts of Isis to protect his limbs. Finally, Osiris achieves rebirth and the play is symbolic of the soul’s journey through the underworld in an effort to be rebirthed too.

Multiple Processions

According to customs, it was common for Egyptians to organize more than one processions. That took place in a necropolis and was a symbol of the soul’s journey through the underworld. During the actual funeral procession, Egyptians used a cattle cart, so to speak, to carry the corpse. At the same time, priests poured milk in front of the corpse and burned aromatic incense.

Mummification

Most researchers agree regarding the steps of mummification that Ancient Egyptians followed.

The primary priority was to prevent the body from decomposing. In order to achieve that, they removed all the organs, except for the heart since the Ib part of the soul resided there. Additionally, a special process had to take place for the brain to be removed as well. Egyptians liquefied the brain with a rod and drained it through the nose. Thereafter, they washed the inside and outside of the corpse with spiced palm wine.

In addition to these techniques, Egyptians dried the body using natron, a natural mineral. They would often dry out the organs as well and then place them in canopic jars or back into the body. Furthermore, this process normally took 40 days. Finally, there were also multiple ways of mummification depending on the rank and financial status of the deceased.

Animal Mummification

Egyptians did not stop with human mummification, though. Animals such as pets were mummified and buried next to their owners. Alternatively, these animals were to help their owners in the afterlife. It is worth mentioning though that pets – and animals in general had another meaning in Ancient Egypt.

The Egyptian religion consisted of a pantheon of anthropomorphic Gods who also had the head of an animal. As a result, certain animals were mummified as a sacrifice or offering to the Gods.

Evolution of Funerary Practices

Considering that Egyptian Dynasties lasted millennia, it should not be a surprise that ancient Egyptian funerals kept evolving. We are next taking a walk through a timeline of Egyptian funeral customs.

Predynastic Burials (pre-3150BC)

The first documented Ancient Egyptian practices are older than the Kingdom of Egypt. Egyptians close to modern day Cairo buried their dead in a very simple manner, in a round grave. They also added a small pot which could contain food for the dead.

Early Dynasties - Mastabas & Coffins (3150 BC – c. 2686 )

During the 1st Dynasty, many wealthier Egyptians started using a mastaba. This was an elaborate mud-brick tomb that had a protected underground burial chamber. Additionally, this style was present both in tombs of kings and the Egyptian elite.

Grave offerings included not only food, but also weapons, jewellery and even furniture! Moreover, Egyptians started using coffins. Interestingly, close servants of kings were also buried close to them. Finally, the first dynasties already used stelas – marking stone slabs – at the entrance of the tomb, in order to indicate whose burial site that was.

Old Kingdom - Mummies & Pyramids (c. 2686 BC– c. 2181 BC)

The Old Kingdom marked the beginning of the use of Pyramids. Interestingly, the oldest form of religious writing in Ancient Egypt resides on the walls of these Pyramids. Furthermore, Egyptians still used mastabas and mummification to bury high ranking officials or the elite.

Architecture wise, Egyptians started using the false door technique in burial chambers or outside of the tomb. That was a sculpture of a door, thus, not functioning. Moreover, they mostly used them as praying spots but also a site for offerings. Close to the end of the period, Egyptians also started to add inscriptions in the inside of coffins and sarcophagi. Around the same time, walls were illustrated with offering decorations, not individuals.

Middle Kingdom - Shabti Figurines (2055 BC – c. 1650 BC)

Mummification continued also during this period. However, commoners didn’t get elaborate burials and weren’t always mummified. Grave offerings for lower classes could include just some food, beer and wooden tomb models. These tomb models were wooden depictions of everyday life of the deceased, such as boats and agriculture.

It was also during the Middle Kingdom that the Shabti (or Ushabti ) figurines were in use. Although early Shabti figurines were simple, the same is not true for their later versions. The latter even ended up functioning as servants or minions of the deceased. Egyptians had to inscribe the name of the owner on the figurines, otherwise the Shabti could not carry out the deceased orders.

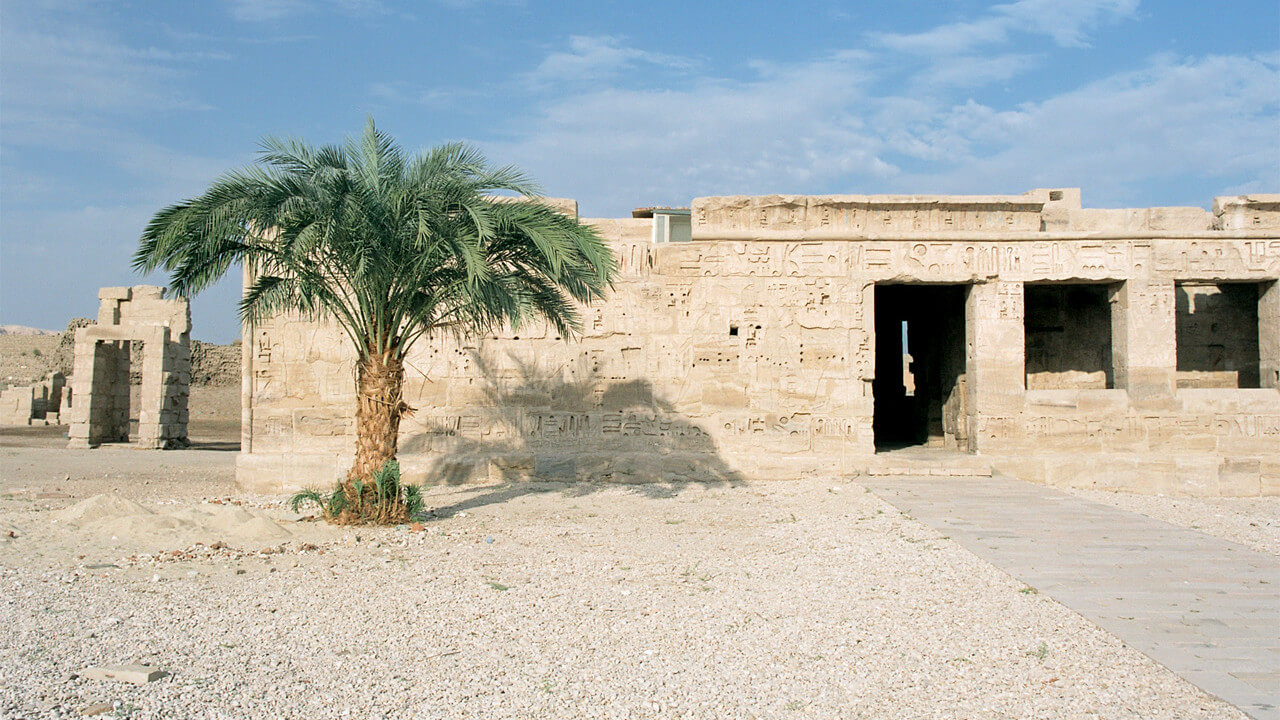

New Kingdom - Valley of the Kings (c. 1550 BC – c. 1077 BC)

The New Kingdom marks an important shift in burial practices. Egypt’s rulers stopped using Pyramids but instead opted for the Valley of the Kings. Specifically, their burial chambers were excavated in solid rock, containing multiple rooms.

Moreover, the western bank of the Nile close to Thebes became the default site for royal funeral rituals. Priests would be in charge of such ceremonies. The Valley of the Kings is home to at least 63 tombs that have been found there. Furthermore, it became very well-known after the discovery of the tomb of King Tutankhamun, due to its connection to the curse of the Pharaoh.

This curse supposedly brings misfortune, illness and even death to people who disturb the tombs of Pharaohs. However, no curse-related inscription was uncovered in King Tutankhamun’s tomb.

Read more

We hope you learned something new regarding this country’s death practices!

Did you enjoy learning about these ancient rituals? If you want know more about medieval and modern Egyptian funeral practices, feel free to check out our article! For more on the nearby Nubian Pyramids and their relation with Ancient Egypt have a look here.

- 5 Different Burial Rites of the Ancient Egyptians – Aditya Chakravarty (2019)

- Aaru

- Abu Simbel

- Adze

- Ancient Egyptian Burial – Joshua J. Mark (2013)

- Ancient Egyptian afterlife beliefs

- Anubis

- Cook, S. (2016). Ancient Egyptian Burial Practices & Connection to the Gods.

- Curse of the Pharaoh

- Edwards, I. E. S. The Pyramids of Egypt. Harmondsworth: 1985.

- Egyptian Mummies

- Early Dynastic Period

- False Door

- Features of Ancient Societies: Death and Funerary Customs in Ancient Egypt – Macquarie University

- Ma’at – Weighing of the Heart

- Middle Kingdom of Egypt

- New Kingdom of Egypt

- Opening of the mouth ceremony

- Prehistoric Egypt

- Pyramid Texts

- Stele

- Ushabti

- Valley of the Kings

- Wooden Tomb Model

- Ricardo Liberato, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- atlantistours, Free Commercial Use, via Pixabay

- anagh, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Wouter Hagens, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Ana Paula Hirama, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP (Glasg), CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Dennis Jarvis, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Jorge Láscar, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Zureks, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Przemyslaw “Blueshade” Idzkiewicz, CC BY-SA 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons

- Myousry6666, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Rama, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- Djehouty, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Максим Улитин, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Mavila2, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- Raffaele pagani, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Nina at the Norwegian bokmål language Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Tim Adams, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Francisco Anzola, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Mohamed kamal 1984, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Nowic talk, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Dr Mahul Brahma, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Максим Улитин, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons