South Korean mortality rates have been steadily rising since 2009 and in 2018 reached the highest in the past 20 years (582,5 deaths per 100.000 people). In addition to that, South Koreans for the most part (56,1%, Consensus 2005) identify as irreligious. However, interestingly enough, there is an intricate culture around death and burial rites. This is historically grounded to traditional Shamanism and Confucianism in South Korea as well as foreign cultural influences. With this article we explore all that but also discuss Korea’s shift to modernity, cremation and the rise of its death industry, examples of which are beaded ashes and mock funerals.

Traditional South Korean death culture draws inspiration both by Shamanistic and Confucian principles. Moreover, these principles originated from periods of Japanese occupation, Chinese influences as well as indigenous traditional practices.

For instance, depending on the season of the year (Korean summers can be quite hot!) the body of the deceased can be kept at home for three days while it is being prepared for burial. Commonly, the exact time of death can be quite significant to South Koreans. Some relatives even place a piece of fabric (usually cotton) next to the nose of a very sick relative in order to determine the time of death as accurately as possible. Immediately after the person passes away, close relatives cover them in a white cloth.

Shamanistic rites focus heavily on the importance of the soul’s passage to the afterlife. For example, traditionally souls that linger in this world (because they got lost!) may start bringing severe bad luck and misfortune to their community. Additionally, Koreans may use scented water, among others, in order to cleanse the body and the soul of the recently departed. At the same time, members of the family, especially the oldest male, have responsibility over the preparations of the shrine. This is where the body of their relative is going to be kept.

In certain Shamanistic traditions, family members also spread cotton cloth across the room. After that they summon spirits of deities in order to help the soul of the dead with their journey to the afterlife.

But what about Confucianism and South Korea?

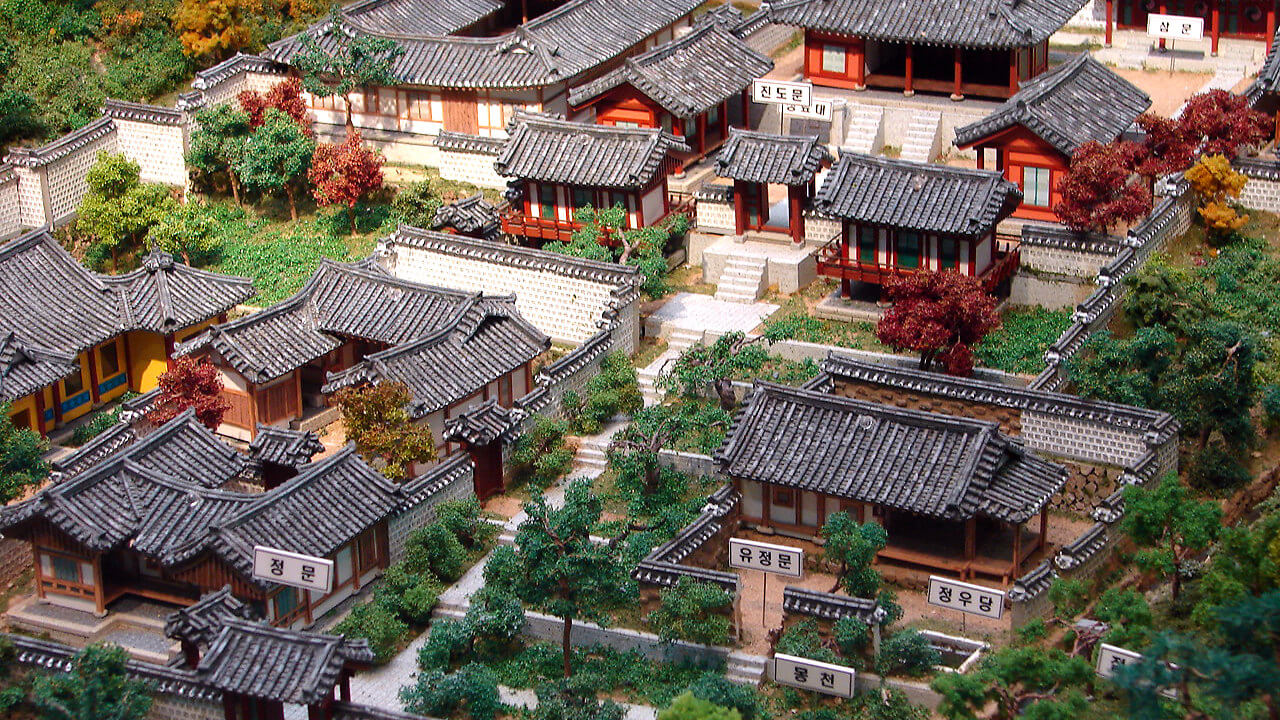

During the Joseon dynasty (1392–1897), Confucianism dominated Korea, influencing every aspect of Koreans’ life – and thus also death. Moreover, Confucianism offered structure and specific instructions so that Koreans could provide the correct death rites to their deceased relatives. Some of the most characteristic influences of Confucianism on Korea’s burial practices are the home funerals and searching for a specific burial site.

Moreover, Confucian principles influenced the way that the loved ones are going to mourn the deceased person. This could officially last for up to three years. Additionally, another example is the Jesa ritual, a memorial service taking place on the death anniversary. Koreans prepared special food for this ceremony including wine, rice cakes, three colors of vegetables and taro soup. However, such memorial services were only some of the ancestor rituals that took place in South Korea. Finally, similar rituals could take place for up to five generations after the death of a relative.

Although these rites are slowly being reformed in modern South Korea, they still play an important role in the life of the family members of the deceased. Finally, all of the above show the long history of Confucianism and South Korea.

As we mentioned above, Confucianism in South Korea supported that a specific burial site for each person was important. Specifically, finding the perfect spot for a grave can also be of extreme importance. It usually was a task for the eldest son of the departed and took place with the help of a geomancer.

Geomancers were professionals in finding the best burial sites depending on the surroundings of the location. Furthermore, according to Confucian principles, this was crucial in order for the soul of the recently deceased to be able to move to the afterlife. Therefore, public cemeteries as we now know them were not really part of the Confucian traditions.

Most Koreans saw cremation as an unthinkable death practice. That is also linked to Confucianism in South Korea and specifically to the significance of filial duty. This refers to the duty of respect that children have towards their parents and it was also present in death practices. For example, cremating their parents, not providing thus the correct burial rites, was a grave offense of this duty.

Confucianism in South Korea did not remain the primary religion. The gradual Westernization of Korean rituals and customs are even influencing the composition of a typical Korean family. In addition to that, the urban lifestyle and the industrialization of South Korea resulted in nuclear families taking over Korean society. Nuclear family refers to the two parents and their children. As a result, many nuclear families abandoned, to an extent, their elder relatives. Therefore, the filial duty had to dramatically adjust to this new reality.

For example, funeral rites were the perfect occasion for Koreans to express their feelings, thoughts and respect in the form of filial piety. If, however, Koreans did not manage to express these while their parents were still alive, then they experienced a lot of guilt.

Of course, feelings of guilt and regret are common for people who are grieving. However, Koreans have to cope in this case with feelings of falling towards their filial duties. In an effort to change that, Koreans often offer a luxurious funeral.

Yet another example of the transformation of traditional death practices was introduced with funeral insurances. According to researchers, these insurances often function as a replacement for funerary gatherings. As a result, the bonding that often takes place in a funeral between grieving family members and friends is overlooked. Summing up, funeral insurances and lavish funerals are new ways for Koreans to fulfill their filial duties which correspond better to their modern lifestyle.

The most profound example of the transformation of Korean death practices was cremation. Specifically, there has gradually been a dramatic shift from burials to cremations in South Korea. For example, a 2000 law dictated that every deceased buried after that year needed to be exhumed within 60 years. As a result most South Koreans started choosing the more approachable option of cremation. Specifically, before this law passed, approximately 60% of South Koreans chose burials, while after 2000, this has decreased to about 30%.

After all, half of the 51 million of Koreans live in the wider Seoul area, the capital city of South Korea and one of the largest metropolitan areas in the world. Therefore, due to lack of space, cremation started steadily becoming more popular. This is also before taking into consideration the implications that the COVID-19 pandemic and its mortality rates may have for a densely populated country like South Korea.

In addition to the above, there were originally no restrictions as to where South Koreans could scatter the ashes of their loved ones. With cremation becoming dramatically popular though, Koreans needed to address this issue. As a result, the South Korean government made corresponding laws in 2006. Finally, it is worth pointing out that the rise of these practices happened at the same time when the irreligious population of South Korea increased as well.

We already discussed how cremation became popular replacing burials. An additional sign of transition towards modernity is the location of the funeral. Specifically, funerals nowadays mostly take place at funeral houses or hospital mortuaries – especially since many people die now at the hospitals instead of their houses. This was not the case, though, until the 1980s, since funerals mostly took place at the deceased’s home.

Interestingly, the rise of funeral houses can be linked to specific housing issues in South Korea. For example, after the 1980s most Koreans live now in apartments or in terraced houses. However, before that time the most usual form of housing was the madang. This refers to stand-alone houses with a proper outdoors space where relatives gathered up for the funerals. With most Koreans living in apartments it is more difficult to have at-home funerals.

Additionally, another potential reason for this transition of death practices is linked to the limited burial space we discussed above. Moreover, Koreans started using Columbaria as a burial practice. After all, that could still allow them to properly pay respect to their dead. These changes became particularly dominant in the 1990s. It was also around that time when the media started favoring cremation over burials. For example, they stopped presenting cremation as an example of Japanese Imperialism.

Firstly, a good example of a modern South Korean death practice is the sumokjang. It was just 2004 when sumokjang took place for the first time when a retired professor of Korea University was buried under a tree. The ceremony took place at a memorial park and it was fitting since the professor specialized in forestry. That was the birth of the custom of sumokjang – a type, thus, of green burial.

Sumokjang has since become quite popular in Korea due to how eco-friendly it is as a burial practice. Additionally, it effectively addresses the lack of burial land in South Korea.

We have already mentioned the role of the media in changing death perceptions in Korea. Additionally, we discussed the rise of funeral services, funeral homes and even funeral insurances. All of these are examples of a professional, well-organized death industry in South Korea.

Moreover, researchers have highlighted the story of a sick man with an infectious disease. As a result of his sickness he could not attend the funeral of his mother. Due to the filial duties we focused on above, the man felt very guilty, even calling himself a pulhyoja. This is a specific South Korean word that describes a person that has not fulfilled their filial piety. Stories like that are broadcasted as actual advertisements by the South Korean media.

Therefore, the death – or funeral – industry profits by helping both the dead and the living. In addition to that, South Korea even offers mock funerals. This refers to people attending their own “funeral”, even laying in a casket.

Over 25.000 Koreans have attended their funerals as a way to appreciate life more. Such services are often advertised as a lesson of dying well. Other potential reasons are reconciling with their past and realizing that they will be missed. Finally, this also aims at reducing the high suicide rates of the country.

Nothing describes better the growth of the funeral industry in South Korea, than the practice we focus on next.

This, at first glance, morbid or confusing question relates actually to a very intriguing, fairly new burial practice in South Korea. Most South Koreans, would place the ashes of a loved one in an urn. However, around 2012, South Korean companies started turning human ashes into colorful beads. These beads come in pink, black, and shades of blue-green and cost around 900 USD.

This practice is gaining in popularity in Europe, Japan and the USA, but not that much in South Korea itself. That is perhaps so because many South Koreans see this practice as disrespectful towards the deceased. After all, this practice does not let them to be naturally integrated into their environment.

Furthermore, to partially answer the question above: no, you cannot wear your mother. For better or worse, these beads are not turned into actual jewelry. Instead, they are placed in jars or plates that family members can keep in their living rooms.

We hope you learned something new regarding Confucianism and South Korea as well as its death practices!

If you want know more about Danish funeral practices, feel free to check out our Denmark article!

The average mixed death rate in South Korea is 5,7 per 1.000 people (2019).

The time of cremation or burial depends on the deceased’s religious beliefs. However, usually funerals take place on the third day upon one’s death.

According to the 2005 census, most South Koreans (56,1%,) identify as irreligious. Christianity (27,6%) and Korean Buddhism (15,5%) are coming next. Interestingly, Christianity is slightly increasing while the latter significantly decreasing in recent years.

South Korea’s rate of utilized organs was 9,22 per million people (2020). Although this may seem low it represents 100% of all the deceased donors.