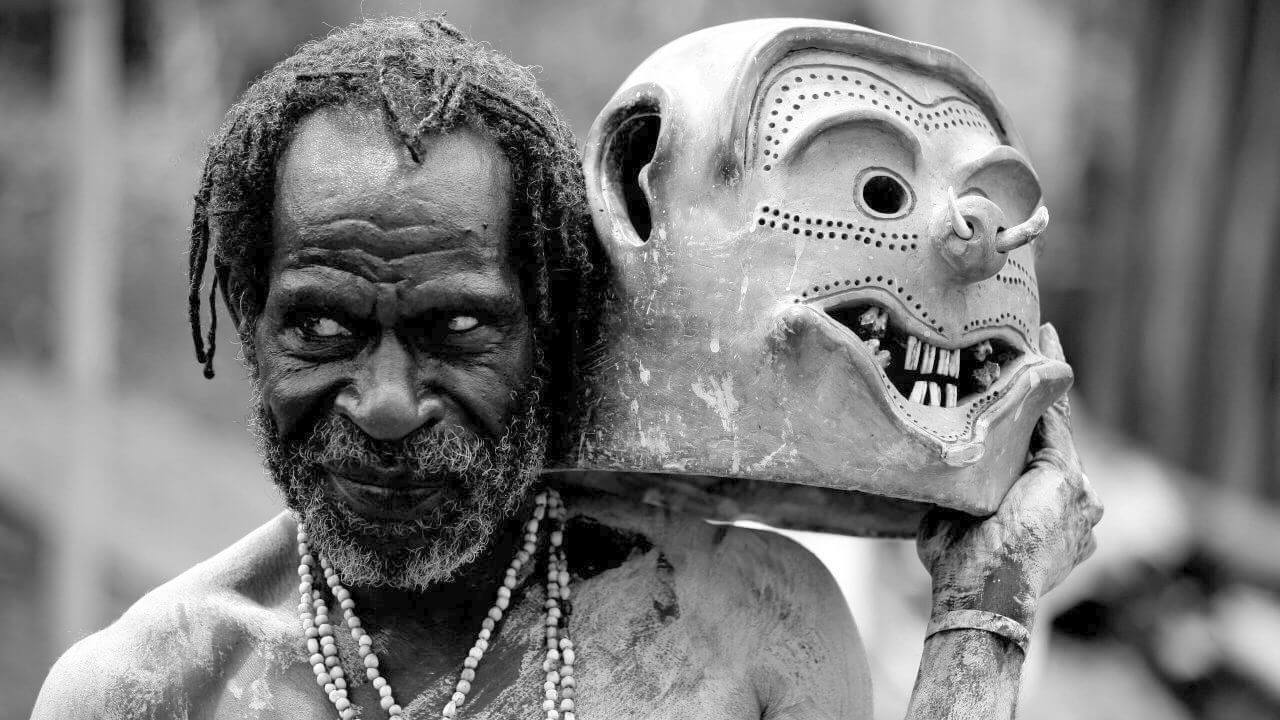

Papua New Guinea is a Melanesian country with rich culture, unexplored nature, and hundreds of tribes! This article takes us to forests and highlands, while we explore the tribal death practices of Papua New Guinea.

The practices we describe in this post, though gruesome and violent, highlight the human necessity to grief. From cannibalism to witch hunts, Guinean death practices are some of the most diverse in the world.

The basis of most Melanesian tribal death practices is the animistic conviction that everything in the natural world has a spirit. Also, death is not the end, but a very important transition to the next, invisible realm. Guineans believe that the living may not see everything, but the dead do! Therefore, they remain parts of their communities.

The majority of Guineans nowadays is Christian. However, Papua New Guinea is home to the second largest number of uncontacted peoples in the world. Therefore, indigenous beliefs and death customs remain extremely significant. Finally, most of the Guinean tribes were historically not worshiping spirits, ancestor or effigies but instead co-existed with them.

Melanesian animism is nicely present in the belief of the Huli Clan that supports that malevolent spirits live in the earth and rocks. So in an effort to protect the body of the their loved ones, Huli do not bury the corpse in the earth. Instead, they are using mortuary platforms. Moreover, when someone dies they place their corpse on a wooden platform in the garden and let nature take over from there.

These mortuary platforms are quite tall, reaching even eye-level height for the Huli. However, for other tribes that varies. For instance, tribes of the Goilala district build mortuary platforms twice as tall as the dead. This is way the spirit can also easier reach the nearby Mount of Albert Edward, which was the designated destination for spirits. Finally, after the complete decomposition of the flesh, they place the bones of the deceased in a nearby cave.

Post-mortuary cannibalism is not unique to the Fore people of Papua New Guinea. Amazon tribes have also been known for their cannibalistic practices and specifically for endocannibalism! This refers to cannibalism performed by members of the same community or family as the deceased.

Fore men ate the flesh of the deceased, while the women and children ate the brains. This practice of cannibalism was also a way of honoring the dead. Furthermore, the Fore believe that it is better to consume their dead, rather than let maggots do it. They also thought that women were more able to successfully contain the malevolent spirit of the dead. Because of that, they were the ones that had to eat the brain after cooking it with ferns.

By eating their dead, the Fore were honoring them.

Although the Fore focused on dealing with the evil spirits of death, they did not account for the physical consequences cannibalism has. For example, certain proteins of the brain cause a specific form of incurable brain disease, known as Kuru, meaning “trembling”. Moreover, it is a form of neurodegeneration that causes lack of coordination, loss of muscle control and in some cases, attacks of laughter. Because of that, it earned also the name laughing disease.

During the 50s and 60s, a Kuru outbreak turned into an epidemic mostly among Fore women. The tribe got so worried that they feared potential extinction! Therefore, they abandoned cannibalism as a tribal death practice. Due to the extremely high incubation period of Kuru, the last documented case might be more recently than what you think. Researchers debate whether the most recent Kuru victim died in 2005 or 2009, even though the practice has been abandoned for decades!

According to this tribal death practice, mourners used white clay on their skins when a man died. Additionally, they threw themselves at the body or even hit themselves with heavy stones. The day after, they buried the body under the thatch hut of the deceased.

Moreover, the widow had to live there in seclusion, neither to be seen by other villagers or talk to them. If she had to leave the house though, she had then hide behind a specific white fabric, called tapa.

This usually lasted for months after the death of her husband! During this time, the widow slept on the shallow grave of her husband, and made sure that the deceased was comfortable. In order to do that, she was occasionally removing maggots from the corpse of her husband with her hands!

Furthermore, other women would visit her to help with making a mourning vest (‘baja’). Finally, once the seclusion period was over, the widow wore her baja during a ceremonial feast (‘tepurukari’). The feast would also welcome her back to the community. In some rare cases widowers would perform this death practice too upon the death of their wife. Additionally, other relatives might abstain from certain activities or the consumption of specific foods as a sign of grief.

One of the most extreme and controversial tribal death practices used to take place in Lemakot, northern New Ireland. According to the local practice, upon the death of a married man, other men strangled the widow. After that, they would add her corpse to the funeral pyre of her husband.

This extreme form of cremation aimed at aiding the spirits of the couple. In other words, they wanted to reunite the couple in the afterlife, so that the husband does not have to wait alone. They did make an exception to this cruel custom, though, for mothers who were still breastfeeding.

Finally, it is worth noting that the Guinean government has now outlawed this death practice.

The final of the tribal death practices we discuss on this post, has also been outlawed by the Guinean government. We are referring to sanguma.

Specifically, tribes of the Chimbu province in the Central Highlands, did not just seek a cause of death. Instead, they tried to identify who did. Sanguma is a tradition that supports that malevolent spirits are often responsible for people’s deaths. These spirits also take the form of a rat or of fox in order to enter humans. Moreover, they feed off their internal organs, using them, in a way, as host organisms. As a result, the person, who in most cases is an old woman, gets sick and eventually dies.

Therefore, the tribe needed to identify the spirit-infected old woman and kill her. This way, they thought they would also kill the malevolent spirits. Sometimes, though, no-none was suspected of being possessed by spirits. Subsequently, the community signified that by food exchanges with the family of the dead, showing them also that there are no suspicions of malevolent spirits.

Although the practice is illegal, cases of murderous mobs launching witch hunts in the name of sanguma are documented until 2019. Finally, many human rights groups have expressed their outrage about the practice.

We hope you learned something new regarding this country’s death practices!

Finally, Guinean groups are not the only ones practicing post-mortuary cannibalism! So feel free to check out our Brazil article on endocannibalism of certain Amazon tribes. For more indigenous death practices and beliefs from neighboring countries we suggest our Australia article, focusing on Aboriginal customs.

The average mixed death rate per 1.000 was 7,427 in 2018. That is for both men and women. The exact number is hard to estimate because of the large numbers of uncontacted peoples.

As this article has highlighted, there is a vast variety a tribal death practices. Therefore, the timing of the funeral depends heavily on the practices of the tribe or that particular community.

Papua New Guinea has a very mixed religious population. The most dominant religion is Christianity, with multiple denominations being present. However, ancestral veneration and animism are often practiced next to these religions. There is no state religion.

It is unclear whether there is an official organ registration or donation system in Papua New Guinea. After a series of violent crimes and abductions, there was a rumor that people are kidnapped for their organs. However, the authorities denied that and said that organ transplantation does not occur in any case.