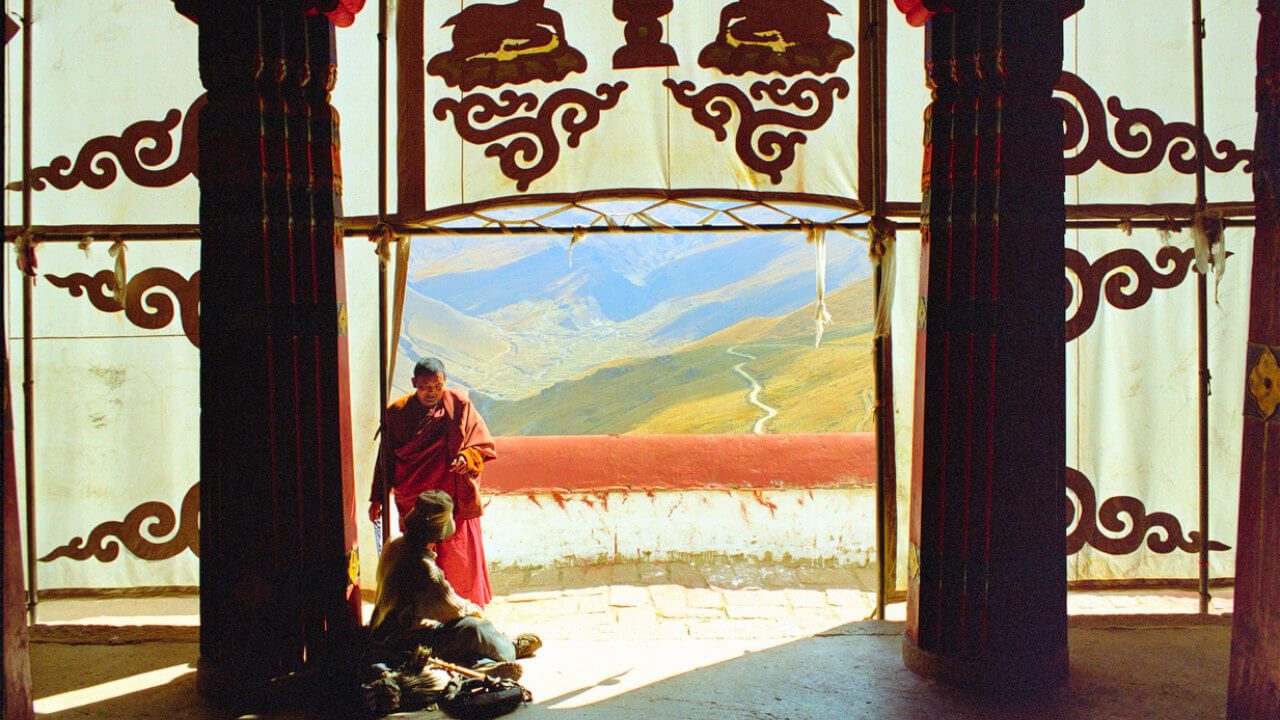

Tibet

Celestial Burials & Hierarchy of Practices

Introduction

Tibetan funeral practices are extremely interesting because of the famous celestial burials. You may have heard those also as Tibet’s sky burials However, less is known about the hierarchy of death practices linked to social status. In this article we explore both of these aspects of Tibetan death perceptions and customs.

Firstly, we discuss the mysterious Bon religion. After that, we focus on Tibetan Buddhists, their beliefs about death and their funeral practices. Interestingly, funeral rites almost always follow a strict hierarchy, with the local Lama directly influencing them with his divination.

Bon Religion

The Bon religion predates Buddhism in Tibet according to evidence found in the ancient Zhang-zhung language. Buddhism spread across Tibet around the 7th Century AD. Furthermore, it started posing a threat to the Bon religion since Buddhists thought that Bonpos, followers of the Bon religion, practice black magic. However, the Bon religion, including its views on death, survived the Buddhist opposition.

Bonpos were quite afraid of the souls of the deceased. So in order to help the soul’s transition, they devised a complex set of rituals. Firstly, the family needs to inform a Lama about the dead individual’s details: name, age, exact time of death, year of birth and animal sign. Then, the Lama can identify the status of the soul in the afterlife. As a result, he can also decide what rituals exactly need to take place.

Bon Funeral Rituals

These death rituals and customs include, but are not limited to, the following:

- The family placed the favorite belongings of the deceased outside the house in case the soul decided to return.

- Additionally, they organized the weekly Bdun Tshigs ritual (translating to ‘Segment of Seven’). Bonpos believed that they needed to provide food to their close friends and other family members.

- Thereafter, relatives prepared the Bzhi Cigu ritual (‘49 Days’) when they burned food on a pan outside of the deceased house. That is based on the belief that the soul may come back to eat the burned meal.

- Furthermore, three days after death, and then annually up to ten years, Lamas read prayers for the dead and made offerings. This ritual’s name is ‘Tranquility & Wrath’ (Zhi Khro).

- Finally, the mourning period is one year. During their time of mourning Bonpos do not wear new clothing. Also, they avoid taking part in celebrations.

Death in Tibetan Buddhist

Most of us know perhaps that Buddhism does not see death as the end, as the spirit lives one. Specifically, Buddhists believe that the spirit experiences Bardo, which translates to intermediate state. This is a crucial phase between life and death that may last up to 49 days. Additionally, Buddhism supports that the living can then still influence the spirit of the dead.

Moreover, there are three Bardos: one represents the exact moment of death (‘Chikhai). During the second Bardo, Buddha appears to the spirit through visions (‘Chonyid’). Finally, the spirit experiences intense hallucinations that eventually lead to rebirth (‘Sidpa’). Similarly to the Bonpos, the family of the deceased and monks perform various rituals after a death. In some cases, relatives give away all the earthly possessions of the deceased. This makes sure that the spirit of the deceased has no attachments to this world.

Celestial Burials – The Philosophy

Sky or celestial burials, embody many principles of Tibetan Buddhism. In a nutshell, these burials allow vultures to eat the body of the deceased. Tibetans believe that vultures are attracted by the bodies of those who are sinless. Additionally, they see these birds as holy and believe that they feed exclusively on human corpses.

If you want to avoid any graphic content click here to skip ahead to traditional stupa burials.

Bones and other remains are also important, since they may represent a sort of attachments. Moreover, strangers tourists, family members may not be present during the burial. This is so because they could stop spirits from moving to the afterlife.

Celestial Burials – The Practice

The rituals of a celestial burial begin immediately after the death of a person. Close relatives cover the body with a white cloth and leave it in the house for three to five days. Both family members and monks try to assist the spirit: Relatives help by stopping all activities so they allow the spirit to go in peace. Monks contribute with praying at an altar.

After that, the family arranges for the corpse to be transferred to the platform of the celestial burial. This is usually in the mountains, away from any communities or villages. They then strip the dead naked and place the body in a fetal position. At the same time, Lamas or monks are chanting prayers and scriptures (‘sutras’). The monks also use a special kind of smoke to lure the vultures, to make sure that the corpse will be consumed.

Flesh as a worldly attachment

Tibetans leave the body there until there is no flesh left. After that, they gather the bones and either cremate or ground them into a powder. The family uses the ashes to make bread that they feed to the vultures. Both approaches make sure that no earthly attachments are present and that the body of the deceased has been returned to nature.

Alternative Tibetan Funeral Practices

Sky burials are still common in Tibet but they are not the only forms of funerals linked to Buddhism. Moreover, there is a hierarchy of burial practices in terms of status and honor.

Stupa Burials

A stupa is a Buddhist monument signifying often a sacred burial. Designs of stupas vary from very simple (wood, clay) to very elaborate (gold, silver). In Tibet, stupa burials are the most sacred burial practice and are reserved only for the Dalai or Panchen Lama. The body of such an important religious figure is embalmed. In some cases, gold flakes and saffron are placed on top of the corpse, as a sign of respect. Only then they place the dead in the stupa.

Cremation

The following, hierarchically speaking, burial practice is cremation. It is a common practice for monks and wealthy people. Tibetans may use these cremated ashes to make Tsatsas which are are clay imitations of sacred objects, deities or symbols. If a person of lower status dies, they are cremated and their relatives usually scatter the ashes in a river.

Water Burial

Tibetan water burials also use white cloths to wrap the corpse. The family then places the body in a river so that the stream takes it away. Water burials are generally inferior to sky burials. Therefore, it is usually members of the lowest classes that practice this custom. However, in regions where sky burials are not prevalent, water burials are much more common for the average Tibetan.

Inhumation

Earth burials, or inhumation, are perhaps the lowest form of funeral practices in Tibet. Buddhists choose for inhumation only if someone dies of unnatural causes such as accidents or murder, or by an infectious disease. Such corpses are not pure enough for holy vultures to consume them. In Pre-Buddhism times, earth burials were the most common practice in Tibet.

Cliff & Tree Burial

South Tibet is home to most cliff burials. The corpses are placed in wooden caskets and hanged from a cliff.

Finally, Tibetans from certain areas like Nyingchi, use tree burials for children. They place the wooden casket with the body of a child on a tree. Normally, they also choose trees in remote forest areas in an effort to hide it away from other children.

Considering all the above, it is safe to say that Tibetan Buddhism highlights the significance of understanding how to die. In the words of Lama Zopa Rinpoche:

"Helping our loved ones at the time of death is the best service we can offer them, our greatest gift."

We could not have said it better ourselves. After all, understanding death and the importance of one’s loved ones inclusion is what we also focus on here in Myend.

Read more

We hope you learned something new regarding this country’s death practices!

If you want read more on other Buddhist funeral customs, check out our article on Russian Buddhism. Finally, for more on sky funerals you can check out our article on the Iranian Towers of Silence or the similar Hanging Coffins of the Philippines.

Stats & Facts

The average mixed death rate in Tibet is 4,95 per 1.000 people (2017).

This heavily depends on type of burial that the deceased receives. Usually Tibetans take care of the bodies within the days following someone’s death.

Census Data

Tibetan Buddhism is the by far the main religion in Tibet (78,5%). Following with a much lower percentage (12,5%) comes the animistic Bon religion (2012).

No independent data is available regarding Tibet’s donor registration system and rates. This is so because Tibet is officially an Autonomous Region of People’s Republic of China.

Life Expectancy

In 2020 life expectancy reached 71,1 in the Autonomous Tibetan Region (Tibet), according to the regional government. This is also double the years, compared to 1951’s score of just 35,5!

- Average life expectancy in Tibet reaches 71.1 (2021)

- Death around the world: Tibetan funerals and sky burials (2016)

- Ishii, H. (2000). Bon, Buddhist and Hindu life cycle rituals: A comparison. Senri Ethnological Reports, 15, 359-382.

- Phowa: A Tibetan Buddhist’s Conscious Dying Meditation – Juniper Quin (2015)

- Religion in Tibet

- Skorupski, T. (1988). Per Kvaerne: Tibetan Bon religion: death ritual of the Tibetan Bonpos (Iconography of Religions, XII, 3. xii, 34 pp., 48 plates. Leiden: E. J Brill, 1985. Guilders 68. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 51(1), 160-161.

- Sky Burial in Tibet and Tibetan Funeral Customs – Kham Sang (2020)

- Tibet

- Tibetan burial customs

- World Data Atlas – China / Tibet

- Andrew and Annemarie, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- liming0759, Free Commercial Use, via Pixabay

- hbieser, Free Commercial Use, via Pixabay

- 沙中灰1, Free Commercial Use, via Pixabay

- hbieser, Free Commercial Use, via Pixabay

- lanur, Free Commercial Use, via Pixabay

- hbieser, Free Commercial Use, via Pixabay

- Ailiajameel, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- FishOil, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- Laika ac, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Göran Höglund (Kartläsarn), CC BY-SA 2.0, via Flickr

- Jako60, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Antoine Taveneaux, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- hbieser, Free Commercial Use, via Pixabay

- Jonang Foundation, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Jan Reurink, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Andelicek.andy, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- FishOil, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons