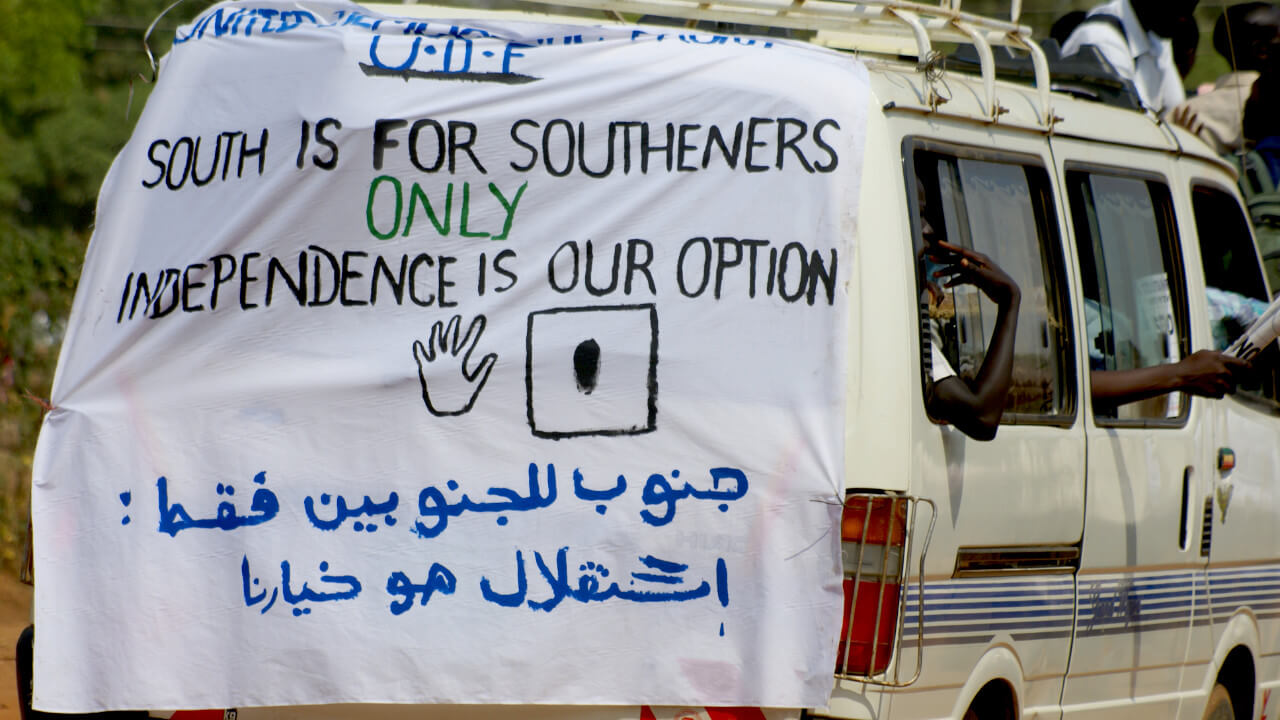

It is worth mentioning that South Sudan has a complicated history with Sudan. Although it is one of the newer Republics it has experienced a tremendous amount of violence and killings. However, we will not approach such issues today. Instead, this article focuses on three different topics in South Sudan. Firstly, we discuss the Acholi death tradition of beer consumption at funerals. Secondly, we explore the mysterious ghost marriages of the Nuer and Atuot ethnic groups. Finally, we conclude with a description of the impact of COVID-19 on burial and mourning practices in South Sudan.

Even before South Sudan gained independence from Sudan, the Acholi tribe had its own distinct funeral customs. According to sources dating back to 1997, Acholi funerals included singing, dancing and eating. More importantly perhaps, brewing and consuming beer is also a big part of the Acholi culture. Therefore, Acholi death customs had a more positive, celebratory nature. However, that was in stark contrast with the somber Islamic funeral rites of Sudan.

Back in the day, Acholis were not allowed to drink beer however. Specifically, due to the dominating presence of Islamic principles in state affairs, alcohol was prohibited in Sudan. The Acholi still assigned meaning to beer, or maraisa, though. A funeral with brewed beer was not a real funeral. It also did not matter to the government whether Acholis consumed beer for fun or as part of the local customs.

It was therefore common that police raided funerals, looking for alcohol. In case they found any they immediately confiscated it. Accounts from these times support that these beer death customs were particularly important to the elder of the Acholi community. They supported that during these more uplifting funerals they masked their pain into happiness.

Specifically, they were very open about drinking their sorrows during the three day funeral event. And although alcohol does not help processing feelings, the Acholi point out that during their beer funerals they get to celebrate their loved one’s life, without having feelings of loss, anxiety and grief dominating the event.

In other words, they choose to say goodbye to their deceased relative in a cheerful manner, instead a sad one.

Before South Sudan’s independence, Acholi’s beer funerals were causing many problems for this ethnic group. Researchers have documented even violent incidents between Muslims and Acholis during these times.

Nowadays, there is a considerable Acholi population that lives away from Sudan. For example, the Acholi of Kiryandongo in Uganda practice much smaller scale funeral customs (lyel). Or at least they do so for the initial burial. Like a few other African societies, the Acholi throw a much larger funeral event on a later stage. In the case of the Acholi, that usually takes place a year after the initial burial.

These celebratory events include both Christian and indigenous religious practices. Additionally, they include the consumption of locally-brewed beer. Members of the clans also join in to make sure that they enjoy beer together. In this respect, even the Acholi diaspora stays very true to its roots and traditions.

Marriage is often defined as a financial or socially accepted sexual union of two individuals. However these elements clearly do not apply when one of these adults is… dead!

The Nuer are Nilotic people residing in South Sudan. According to their customs, if a man dies without an heir, a particular process starts. One of the deceased’s sisters-in law would have to marry his ghost. In other words, one of the wives of the deceased’s brothers needs to accept a ghost marriage. This way the children this woman already has will become the heirs of the deceased.

Another version of this fascinating tradition sees a barren woman related to the dead man replacing him. This relative of the dead man becomes the male – culturally and socially – in their relationship. Therefore, it is not considered a same-sex relationship. In similar fashion as the original custom we describe above, the children of the wife are considered offspring of the dead. In a way this is a ghost marriage by proxy!

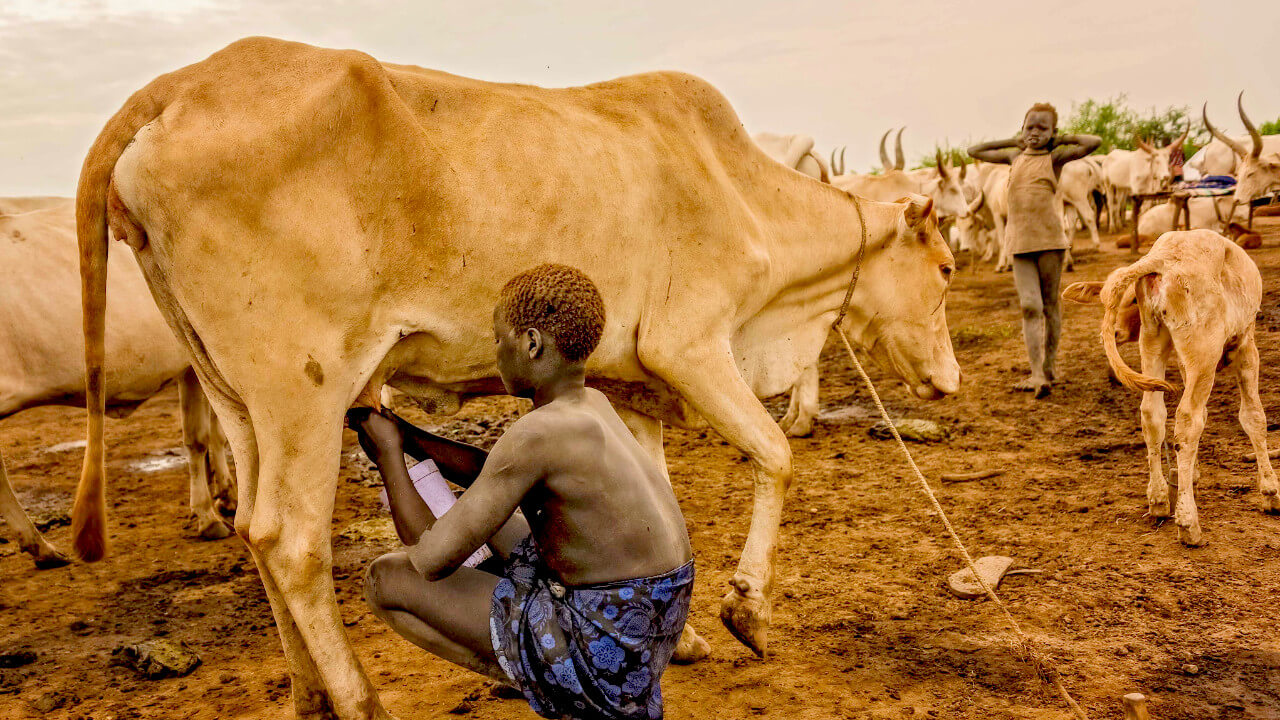

Normally, Nuer men use cattle as currency for weddings and bribes. They also give their cattle to their sons after they die. If the deceased, however, had no heirs, the cattle goes to his brother. In the cases we described above, cattle functions as currency to get a bribe also for the deceased’s ghost.

The main purpose of a Nuer ghost marriage is for the family to acquire male heirs. In Nuer culture it is also crucial to have male heirs, due to the higher position they have in their community. For example, women are not allowed to own cattle. Therefore, a ghost marriage ensures the continuation of their bloodline.

Very similar to the Nuer, the Atuot also practice the death custom of ghost marriages. The main difference becomes visible in case that the deceased had a daughter. In this circumstance, it is very likely that the daughter takes a male role and actually gets a wife.

Trading cattle instead of fighting over has also dramatically reduced male deaths related to cattle-acquisition. That means that nowadays there are more male owners of cattle and therefore, the popularity of ghost marriages has declined.

In addition to these, the Atuot support that they use ghost marriages as precaution to not let the family name die out. Researchers have backed this claim using the Atuot language as evidence. For example, ghost marriage in Atuot can be also translated into “holding up straight”. This refers perhaps to the notion of holding the name of the dead alive. Finally, offspring of a ghost marriage are sometimes discriminated against.

An additional purpose for a ghost marriage has sometimes also a spiritual dimension. In other words, if the spirit is married to someone, he will not seek revenge from the afterlife. Moreover, the oldest brother needs to marry before his younger brothers in the Atuot culture. This applies even if the older brother dies, since his siblings cannot get married.

Some tribes in South Sudan tend to immediately gather up upon someone’s death. They would normally build temporary tents and start collectively working on organizing the funeral. Collective mourning is advised heavily against, though, since the beginning of the pandemic.

That applies also to customs regarding body preparation prior to the burial. Although certain communities bury their dead immediately after death, the body is always cared for. Men wash the body of a man, and women do the same. During the pandemic, communal activities are discouraged. However, people invite a community or religious leader during the body preparation. Authorities in South Sudan recommend the usage of protective gear when handling a dead body of a confirmed case.

Both Muslim and Christian South Sudanese like to attend the burial of a loved one. They even both throw dirt in the grave! During the COVID-19 crisis, traditional burials take place as normal only if the deceased was not positive to the virus. Otherwise the measures propose that these should be much more quiet events.

During the actual funeral many tribes express their grief in physical manners. That includes handshakes and frequent hugging between many relatives. Additionally, according to social norms, it is offensive to not attend the funeral of a friend or neighbor.

Because of the public character of the funerals, South Sudan tried to implement social distancing and proposed that masks should be handed to attendees. The extent of success of such measures at funerals has not yet been studied in the country.

We hope you learned something new regarding this country’s death practices!

If you want know more about the neighboring Sudanese funeral practices, feel free to check out our Sudan article!

The average mixed death rate in South Sudan is 10,342 per 1.000 people (2019).

The funerals usually follow the teachings of the deceased’s religion. Muslims tend to to bury their dead as soon as possible. Christian South Sudanese may wait a bit before burying them.

Around 60% of South Sudan’s population is Christian. Over 32% follows African religions, and there is a 6% Islamic presence. However, Christian and Indigenous religions often intermix in South Sudan.

It is also important to point out that Christianity already reached this region around the second century.

No clear data regarding South Sudan’s donor system is available. There might even not be a system in place since South Sudan is one of the youngest Republics in the world – 2011!